Excellent tools are often born from a developer’s “uncompromising” attitude towards their own pain points. Sintone is exactly this kind of developer. In pursuit of a smoother screen recording and editing experience, he developed ScreenSage Pro from scratch and has maintained an astonishing speed of iteration.

When I first commissioned this article, I didn’t expect Sintone to hold nothing back. From the bizarre bugs of ScreenCaptureKit to practical techniques for high-performance video composition, he lays out every pitfall he encountered and his solutions. This level of honesty is truly a pleasant surprise.

Video is replacing text as the mainstream mode of expression, and good tools are accelerators for creation. Whether you want to develop a similar product or are interested in independent development, this article is not to be missed.

I am Sintone, an independent developer. For the past year or so, I’ve been working on a screen recording and editing tool for macOS called ScreenSage Pro.

Before I start telling the product story, let me briefly explain what kind of software ScreenSage Pro is, and then discuss how its core functions were implemented. That way, after reading this article, perhaps you’ll be ready to build a competitor.

What’s so hard about screen recording?

If you’ve used QuickTime, you might think screen recording is simple: just save the screen content as an MP4, right?

Many developers think this way. Until I released my first product and started making demo videos, I realized the vast chasm between “screen recording” and “a watchable demo video.”

My nightmare workflow at the time looked like this: Record → Drag into CapCut → Manually add keyframes to zoom in on key areas.

It was like manually writing 100 if-else statements in code. Every zoom, every keyframe point, every adjustment of the animation curve required repeated previewing and modifying. Often, after adjusting the zoom ratio, I’d find the transition unnatural; after fixing the transition, I’d find the mouse wasn’t centered.

Besides the tedious editing, there were critical flaws:

- Mouse too small: On high-resolution screens, the audience couldn’t see where I was clicking.

- Lack of interaction: Trying to overlay a webcam for explanation while recording resulted in a breakdown when trying to sync tracks in post-production.

A 1-minute video often took me 30 minutes or longer to polish these details. For a developer, this inefficiency was intolerable.

I was sick of editing videos, so I decided to write code to solve this problem.

ScreenSage Pro was built to solve these problems. Let me tell you how it works.

Recording extra information boosts efficiency by more than tenfold

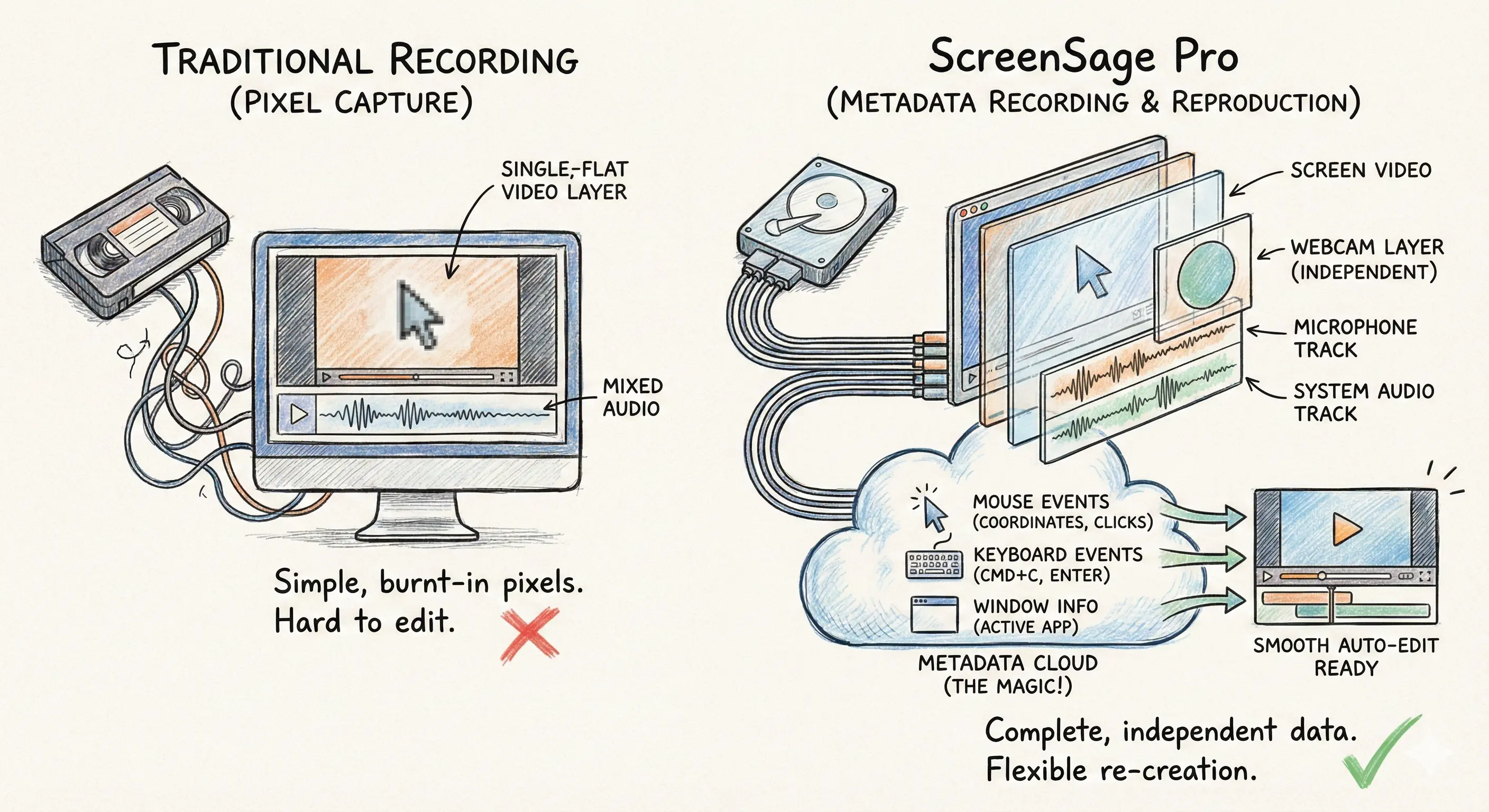

Unlike traditional screen recording software, the philosophy behind ScreenSage Pro is not simple “screen pixel capture,” but “complete metadata recording and reproduction.” Simply put, when the user presses record, we capture not just screen pixels, but a vast amount of metadata. I run several parallel tracks in the background:

-

Multiple Audio/Video Streams (Independent & Synced):

- Screen Visuals: High-resolution, high-framerate clean footage.

- Camera (Webcam): Recorded as an independent layer, not drawn directly onto the screen video, allowing for arbitrary repositioning in post.

- Microphone & System Audio: Independent audio tracks that don’t interfere with each other.

-

Critical “Metadata”: This is the core of “silky smooth automatic editing.” I don’t “burn” the mouse cursor into the video; instead, I record its data every millisecond:

- Mouse Events: Coordinates, click state, style changes.

- Keyboard Events: Did the user press Cmd+C or Enter?

- Window Info: Which App is currently active, window size.

With this raw material, we have the capability to achieve our core experience: “Editing is done when recording is done.” With this metadata, we can do many things:

- 🖱️ Smart Focus: Knowing when and where the mouse clicks allows for programmatic zooming on focal areas, or even adding 3D perspective effects.

- 🎨 Mouse Beautification: Real-time tracking of mouse position and style allows for enlarging the pointer or replacing it with custom graphics during composition.

- ⌨️ Keystroke Display: Capturing keyboard events to automatically overlay key hints (Cmd+C, Enter, etc.) in the video.

Because we capture enough information to recreate the scene, we have immense creative space in post-production, allowing us to unleash our imagination and liberate our productivity. This is something traditional screen recording software cannot offer.

The Start of the Product - Pre-sales

In late November 2024, taking advantage of the Black Friday shopping craze, my first App saw a peak in growth. I thought, since I’m riding the wave, why not borrow a bit more heat and pre-sell this idea? I used AI for 3 hours to name it, design a logo, generate a webpage, and launch the pre-sale. It was done quickly.

I didn’t have high hopes, so I went to sleep.

As you can imagine, the pre-sale was a success. The next morning, I checked my inbox as usual and found a “You made a sale” email. I successfully received $69. Over the next few days, I received about 20 more orders. “Okay, this can work.” So, I decided to build it. The release date for version 1.0 was set for April 1, 2025, four months later.

Starting Development: Recording and Video Composition

Let me briefly introduce my development background.

I have been working professionally for 8 years. For those 8 years, I was an Android developer, occasionally dabbling in Mac software development out of interest, but always stopping at the Demo stage. In September 2023, I was successfully “optimized” (laid off) by my company, and with my severance pay, I happily started developing my first commercial Mac software.

That is to say, regarding Mac development, I was an amateur. When I started developing the screen recorder in February 2025, I was still an amateur, and I remain one today. So if there are any inaccuracies in this article, please feel free to correct me.

Next, I will talk about some core points of developing this App from 0 to 1, and some experiences from 1 to 2.

Feasibility Study - Testing Based on Open Source Projects

December 2024.

At this point, the pre-sale was roughly successful, but I was very anxious. I knew nothing about screen recording, nor about how to compose video after recording. Furthermore, in the second half of December, I was going to Bole and Yili for a trip with my girlfriend, and in January, I had to launch the iOS version of my first software. The time left for this big project was only February and March. Was two months enough? My heart was beating fast.

I couldn’t just go on a trip like that. To put my mind at ease, I downloaded an open-source project that was somewhat popular at the time called QuickRecorder. I added listeners and recording for mouse events at the start of the recording. In the video preview player, I read the mouse click events and positions. I briefly studied VideoComposition to make it zoom in by a certain factor based on the target point center. Soon, a version for this feasibility study was born.

// Pseudocode: Logic during MVP verification phase

struct MouseEvent {

let time: TimeInterval

let point: CGPoint

}

// 1. Primitive mouse monitoring

var mouseLog: [MouseEvent] = []

NSEvent.addGlobalMonitorForEvents(matching: .leftMouseDown) { event in

mouseLog.append(MouseEvent(time: Date().timeIntervalSince1970, point: event.locationInWindow))

}

// 2. Simple composition logic (AVVideoComposition)

let composition = AVMutableVideoComposition(asset: asset) { request in

let currentTime = request.compositionTime

// Find mouse clicks near the current time

if let click = mouseLog.first(where: { abs($0.time - currentTime) < 0.5 }) {

// Core validation: If there is a point, brutally zoom in 2x

let transform = CGAffineTransform(scaleX: 2.0, y: 2.0)

.translatedBy(x: -click.point.x, y: -click.point.y) // Center it

request.finish(with: request.sourceImage.transformed(by: transform), context: nil)

} else {

request.finish(with: request.sourceImage, context: nil)

}

}This code made the video zoom in 2x centered on the click point when playing back at the moment of a mouse click. No transitions, no animation, just a hard zoom. Although it was primitive to the core, it gave me immense confidence to start. I knew the workflow was viable, which meant it would likely work.

At this stage, I understood nothing about screen recording development concepts and had a vague idea about video composition, but this test told me: this can be done.

The First Line of Code - Screen Recording

It was February 2025. My girlfriend and I returned from our trip, and the iOS version of the clipboard app was released as scheduled. At that time, AI hadn’t yet shown its full power and could only be used as an assistant.

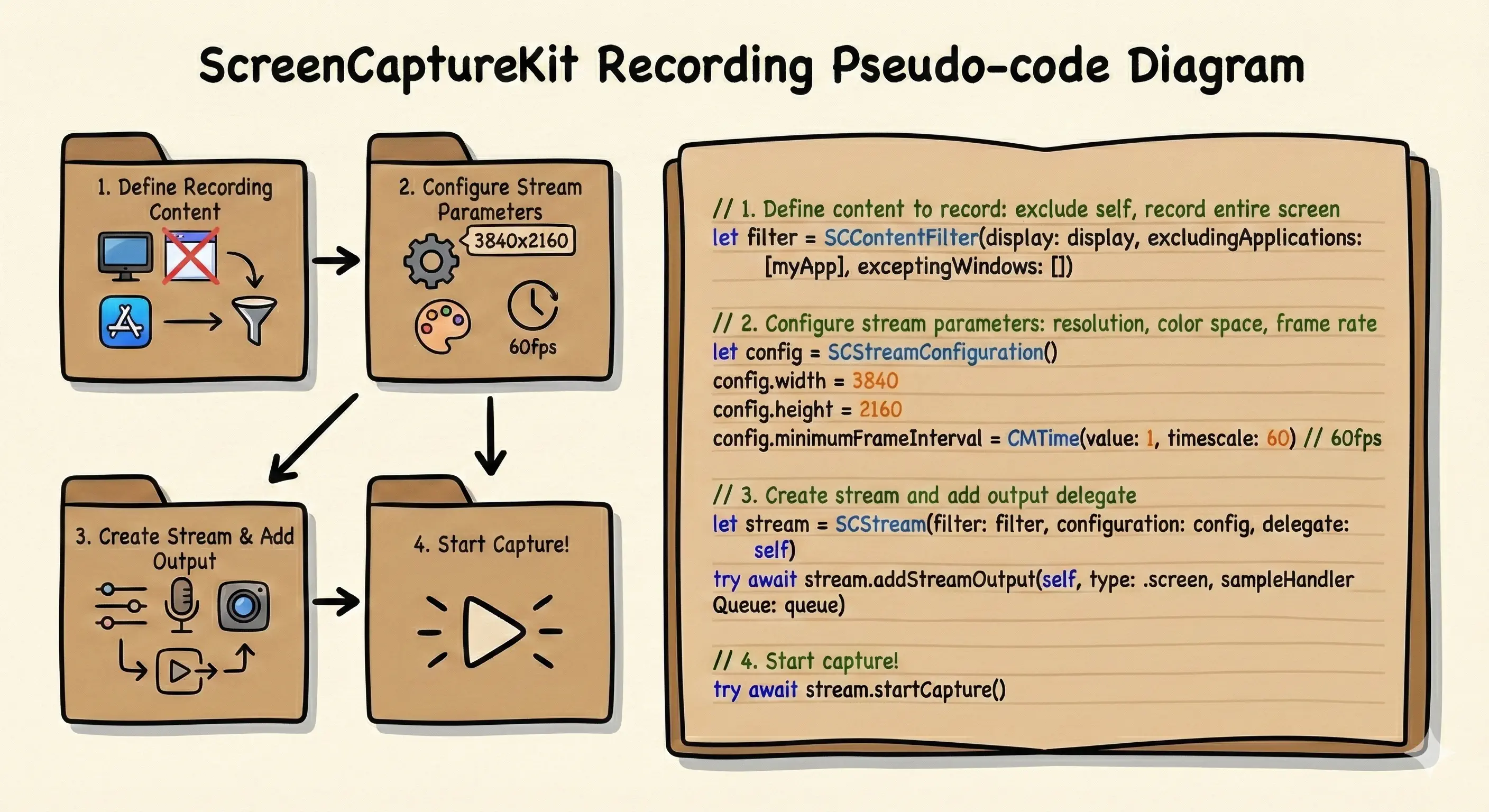

My way of using AI back then was not to let it write code directly, but to chat with it and learn through it. Through constant chatting, I learned about the new framework SCK (ScreenCaptureKit), its advantages over traditional recording frameworks, and its convenience.

By this step, my understanding of SCK was much clearer:

| Feature Dimension | Traditional Recording (CGWindowList / AVCapture) | ScreenCaptureKit (SCK) |

|---|---|---|

| Performance | High (Significant CPU/GPU usage, quick heating) | Very Low (GPU-based zero-copy, cool and quiet) |

| Frame Stability | Unstable, prone to dropped frames under high load | Extremely high, system-level optimization |

| Window Recording | Difficult, complex occlusion handling, cannot record background windows | Native Support, windows are unaffected by occlusion or being moved off-screen |

| System Audio | Not Supported (Usually requires installing Audio Driver plugins) | Native Support (Directly capture App or System audio) |

| Privacy Permissions | Requires Screen Recording permission | Only requires Screen Recording permission, supports excluding own window |

| Dev Difficulty | Lots of material, but APIs are old and cumbersome | Modern API, but many pitfalls and scarce documentation |

Relying on chats with AI, I pieced together the first line (segment) of code for screen recording.

Metadata Recording - Mouse Events

To solve the problem, mouse and keyboard metadata are essential.

The mouse is used to track critical click times and locations for zooming and tracking.

This step is simple: start listening when recording begins, define the data structure, and save it to memory.

// Define metadata structure: We need to know "When, Where, What happened"

struct UserActionMetadata: Codable {

enum ActionType { case click, keyPress, windowChange }

let timestamp: Double // Timestamp relative to recording start

let location: CGPoint? // Mouse position

let keyCombo: String? // Keyboard keys, e.g., "Cmd+C"

let activeApp: String? // Currently active application

}

// Listen and record

func startRecordingMetadata() {

let startTime = Date()

// Listen for global mouse events (requires Accessibility permissions)

NSEvent.addGlobalMonitorForEvents(matching: [.leftMouseDown, .rightMouseDown]) { event in

let meta = UserActionMetadata(

type: .click,

timestamp: Date().timeIntervalSince(startTime),

location: NSEvent.mouseLocation,

keyCombo: nil,

activeApp: NSWorkspace.shared.frontmostApplication?.localizedName

)

self.metadataBuffer.append(meta)

}

// Keyboard listening logic follows the same pattern...

}How to Ensure Timeline Synchronization?

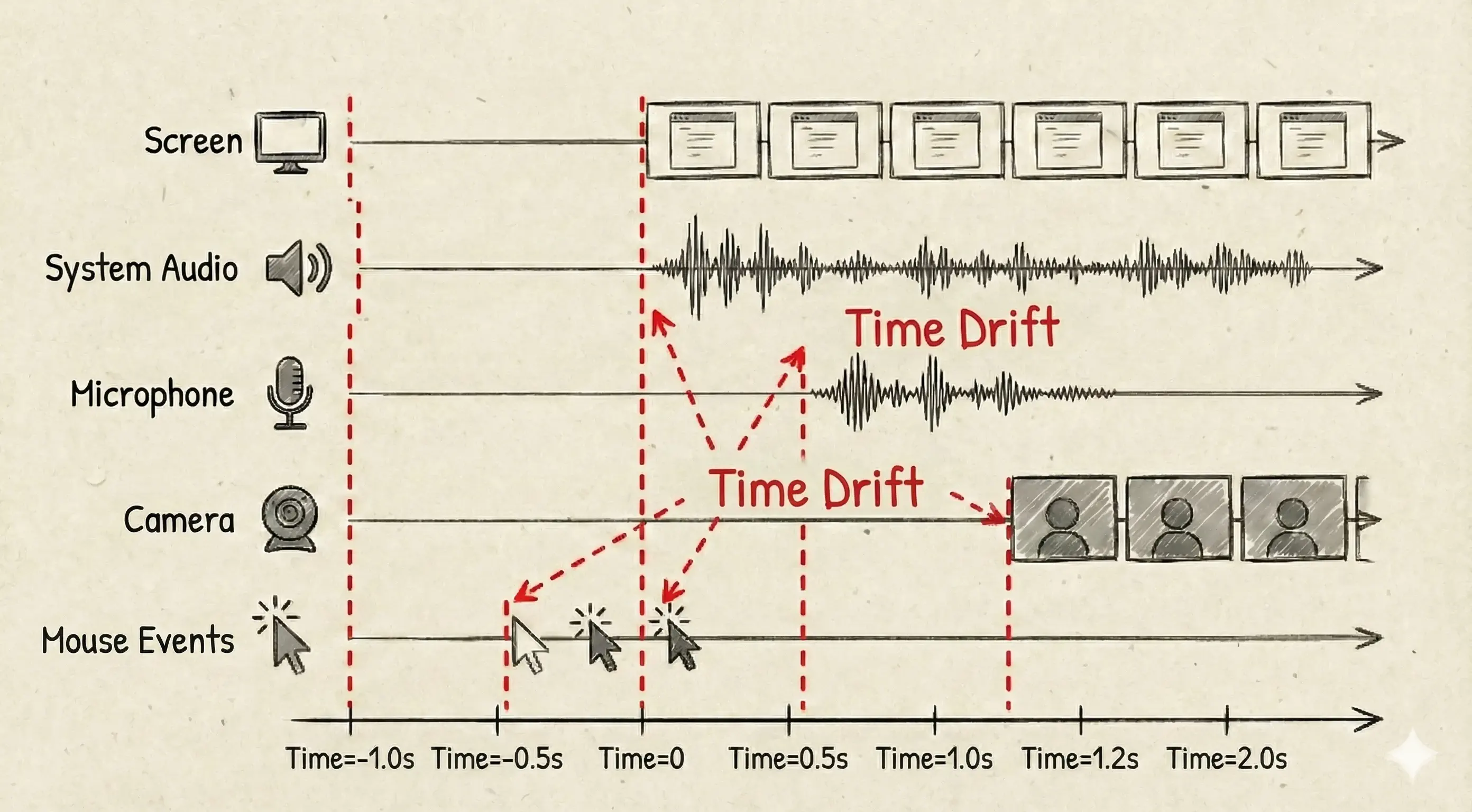

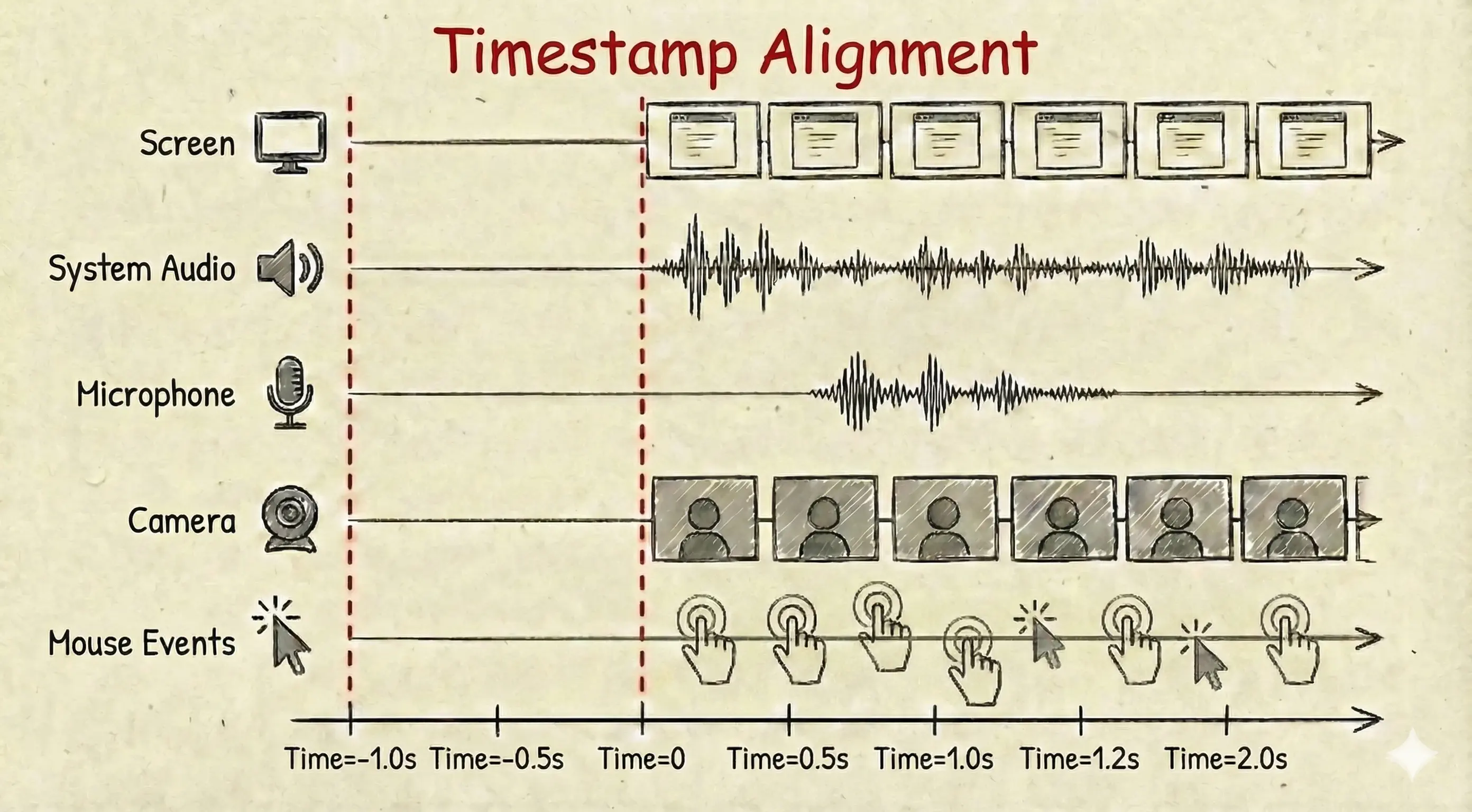

I knew how to record all the content, but the problem arose: from calling “start recording” to getting the first frame, each content stream has varying degrees of delay. How to ensure their timelines are perfectly synchronized?

Screen content and system audio are written into the same video file, so they automatically sync based on frame data PTS (Presentation Time Stamp). However, the microphone, camera, and mouse events are written to different files. How do we sync them?

At first, I naively thought that calling their start recording methods simultaneously would achieve synchronization. Facts proved I was indeed naive. Especially when connecting to external devices, their preparation work can take a long time, making this delay particularly obvious.

After some research, I found the solution was relatively simple: “Just record the timestamp of the first frame for each recording.”

Mouse events are the easiest; just subtract the recording start time from the current time when an event triggers, naturally aligning with the recording timeline. More complex is the synchronization of video streams.

SCK Recording First Frame Timestamp

SCK screen content and system audio are obtained via the SCStreamOutput protocol callback. Each frame of data carries a CMSampleBuffer, which contains a precise timestamp (presentationTimeStamp):

func stream(_ stream: SCStream, didOutputSampleBuffer sampleBuffer: CMSampleBuffer, of type: SCStreamOutputType) {

// Get frame timestamp

let timestamp = CMSampleBufferGetPresentationTimeStamp(sampleBuffer)

// Record first frame time

if firstFrameTimestamp == nil {

firstFrameTimestamp = timestamp

print("📹 SCK First Frame Time: \(timestamp.seconds)s")

}

// All subsequent frames sync based on this first frame time

// ...

}Microphone & Camera First Frame Timestamp

Initially, for simplicity, I used AVCaptureMovieFileOutput to save microphone and camera data. This is a highly encapsulated “dummy-proof” class; add it to the Session, call startRecording, and it generates a file.

Simple AVMovieFileOutput Call (Old Solution):

// Old way: Dummy-proof recording, but no precise control

// 1. Create Output

let movieOutput = AVCaptureMovieFileOutput()

// 2. Add to Session (System handles connection automatically)

if captureSession.canAddOutput(movieOutput) {

captureSession.addOutput(movieOutput)

}

// 3. Start Recording (Writes directly to file, cannot touch per-frame data)

movieOutput.startRecording(to: fileURL, recordingDelegate: self)However, its fatal flaw is being a “Black Box”: It manages writing automatically. I couldn’t know the exact time of the first frame, couldn’t touch individual frames, and couldn’t modify timestamps before writing.

Later, I steeled myself and rewrote everything. I changed to AVCaptureVideoDataOutput (paired with AVCaptureAudioDataOutput).

This path is much harder to walk. You not only have to configure the Output yourself but also create queues, set delegates, and manually manage the AVAssetWriter. But this gave me a “God View”: I could get raw data for every frame and manually correct timestamps.

Although the code volume multiplied, the benefit was that I solved it myself.

Manual Control after switching to AVCaptureVideoDataOutput (New Solution):

// 1. Create Video Output

let videoOutput = AVCaptureVideoDataOutput()

// Key Point: Set delegate, must callback on an independent queue, otherwise it blocks the main thread

let videoQueue = DispatchQueue(label: "com.app.videoQueue")

videoOutput.setSampleBufferDelegate(self, queue: videoQueue)

// 2. Add to Session

if captureSession.canAddOutput(videoOutput) {

captureSession.addOutput(videoOutput)

}

// ... (Audio Output configured similarly) ...

// 3. Delegate Callback: This is where we truly control the data

func captureOutput(_ output: AVCaptureOutput, didOutput sampleBuffer: CMSampleBuffer, from connection: AVCaptureConnection) {

// Here we can get every frame (CMSampleBuffer)

// Perform timestamp calculation, audio-video sync correction

let adjustedBuffer = adjustTimestamp(for: sampleBuffer)

// Finally, manually feed it to AssetWriter

if assetWriterInput.isReadyForMoreMediaData {

assetWriterInput.append(adjustedBuffer)

}

}Stability means low customizability; high customizability often means breaking stability. To get precise control, you have to step out of the system’s “comfort zone” and handle the dirty work yourself.

Although this change was painful, it laid the foundation for subsequent features, such as volume boosting, noise reduction, and audio waveform display, because I could finally touch the raw data.

Video Composition - Data Collected, Making Content Collaborate for Auto-Editing

There are several ways to do video composition on macOS, with increasing difficulty and flexibility:

- AVVideoComposition (Core Animation):

This is Apple’s official high-level API. A bit like making a PPT, you arrange video tracks and set Opacity and Transform.

- Pros: Simple, native support.

- Cons: Average flexibility, only basic move/zoom. Very hard to do “Motion Blur,” “Advanced Transitions,” or “Dynamic Background Blur.”

- Core Image + AVFoundation: Allows applying filters to every video frame.

- Pros: Rich effects (Gaussian Blur, Color Adjustment).

- Cons: If not careful, easily leads to memory explosion (OOM), slow rendering speed.

- Metal / MetalPetal (Final Choice): This is the nuclear option. Calling the GPU directly for rendering. I ultimately chose the open-source framework MetalPetal. It is a Metal-based image processing framework developed by Yu Ao. Why choose it? Because ScreenSage Pro needs to process 4K 60FPS multi-layer visuals (Screen + Camera + Background Blur + Mouse Effects) in real-time. Only Metal can complete this task without turning a MacBook into a “helicopter.” By writing custom Shaders, I can precisely control every pixel and implement that silky smooth Motion Blur effect, which is key to making the video look “professional.”

At different stages of the App, I sequentially used these three methods:

- During the idea verification and first MVP version, I used

AVVideoComposition, which helped me quickly achieve a simple acceptable effect. - Later, I had some advanced requirements like Gaussian Blur, adding shadows, and multi-layer blending, so I switched to

Core Image + AVFoundation. - Even later, I had ideas for 3D effects. Core Image couldn’t achieve perspective effects, so I switched to Metal.

Regarding how to choose between them, I think the information above is helpful enough. Here I will just briefly introduce MetalPetal:

// Initialization

let context = try MTIContext(device: device)

let asset = AVAsset(url: videoURL)

// Key method for composition

let composition = MTIVideoComposition(asset: asset, context: context, queue: DispatchQueue.main, filter: { request in

return FilterGraph.makeImage { output in

request.anySourceImage! => filterA => filterB => output

}!

}

// Play composition in video player

let playerItem = AVPlayerItem(asset: asset)

playerItem.videoComposition = composition.makeAVVideoComposition()

player.replaceCurrentItem(with: playerItem)

player.play()Okay, up to now, the core functions of this App have been implemented. Go implement one yourself.

Video Size and Bitrate: How to Make Video Files Smaller?

After releasing several versions, I found that with the same duration and resolution, video files generated by competitors were very small, while mine recorded with AVFoundation were ridiculously large.

At first, I thought it was a resolution issue. Current MacBooks are all Retina screens, recording near 4K physical resolution. But after testing, I found the root cause was that I hadn’t manually limited the Bitrate.

What exactly is Bitrate?

Before solving the problem, we must understand what it is. If a video is a painting, Resolution determines the size of the canvas (e.g., 4K is as big as a wall), and Bitrate determines how much paint budget you are given per second to fill that canvas.

- Resolution determines the physical size limit of the image.

- Bitrate directly determines file size and image fullness. This explains why my files were huge: The system saw I had a large 4K canvas, and to be safe, it defaulted to giving me a whole bucket of paint (ultra-high bitrate). Whether I was painting a complex “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” or just a few words on white paper, it dumped the paint regardless, resulting in an explosion of data.

Why Must We Manually Preset Bitrate?

I had a big question here:

“Why do I have to preset a fixed value for bitrate? Can’t the encoder calculate how much data is needed based on the complexity of each frame?”

Theoretically, it should be “pay as you go”: use more data for complex scenes, less for simple ones. But the problem is, AVFoundation by default acts like a wealthy tycoon with no budget limit.

If we don’t restrict it, in pursuit of even a 1% quality improvement invisible to the naked eye, it will unhesitatingly invest 10 times the amount of data. Especially in screen recording scenarios where the screen is static most of the time, the system’s default high bitrate might lead to filling invalid data most of the time, causing the hard drive to fill up.

Understanding AverageBitrate: Flexible Budget Management

So, we need to set AVVideoAverageBitRateKey.

Note, the key is called “Average Bitrate.” This is easy to understand; we aren’t mandating the size of every frame, but giving the encoder an “annual budget.”

When we set a budget (e.g., 6Mbps), the encoder becomes frugal:

- Screen Static (Off-peak): It saves the unused “budget.”

- Drastic Screen Changes (Peak): Like switching windows or scrolling code, it uses the saved budget to spike the bitrate instantly to ensure clarity.

This prevents uncontrolled size while utilizing the dynamic adjustment capabilities of the encoder.

If We Must Set a Budget, How Much is Appropriate? (BPP)

Too little budget, the picture blurs; too much, the size is huge. Initially, I crudely hardcoded 6_000_000 (6Mbps), but there’s a pitfall: this might be too much for a 1080p screen, yet insufficient for a 5K monitor.

Here we need to introduce a concept: BPP (Bits Per Pixel). Simply put, it decides how much paint (bitrate) based on your canvas size (resolution).

For low-dynamic scenarios like screen recording, 0.05 is a golden coefficient. We can write a simple algorithm to let the program automatically calculate a “just right” budget based on the user’s screen resolution.

Adaptive Compression Configuration:

func makeCompressionSettings(for size: CGSize, fps: Int = 60) -> [String: Any] {

// 1. Set budget coefficient (BPP)

// 0.05 is the sweet spot for screen recording; suppresses size without blurring text

let bpp: CGFloat = 0.05

// 2. Dynamically calculate annual budget (Target Bitrate)

// Algorithm: Total Pixels * FPS * BPP

// E.g., on a Retina screen, calculates to approx 17Mbps, saving more than half compared to system default 40Mbps+

let pixelCount = size.width * size.height

let targetBitrate = Int(pixelCount * CGFloat(fps) * bpp)

print("💰 Budget Calculation: \(Int(size.width))x\(Int(size.height)) | Limit Bitrate: \(targetBitrate / 1000) kbps")

return [

AVVideoCodecKey: AVVideoCodecType.h264,

AVVideoWidthKey: size.width,

AVVideoHeightKey: size.height,

AVVideoCompressionPropertiesKey: [

// Core Stuff: Manually take over the budget

AVVideoAverageBitRateKey: targetBitrate,

// Use High Profile: Equivalent to hiring a better painter for the same budget

AVVideoProfileLevelKey: AVVideoProfileLevelH264HighAutoLevel,

AVVideoExpectedSourceFrameRateKey: fps

]

]

}With this logic, whether the user uses a native MacBook screen or an external monitor, we can compress the file size to the extreme while guaranteeing image quality.

Software Crashes During Recording, User Crashes Too. How to Save the Recorded File?

One day, on X (Twitter), I saw a friend complaining that the predecessor software Screen Studio recorded for 40 minutes but couldn’t save, and he had a meltdown. I know deeply that no program can be fully trusted, even one written by oneself. Even if the logic is considered thoroughly, there is no guarantee against the unexpected. That’s why they are called accidents. So I immediately went to find a solution.

By default, MP4 file header information is written only when recording ends. If the App crashes or the computer loses power in the middle, and this header info isn’t written, the whole file is a pile of junk data.

I looked into HLS and implemented a segmented writing method myself, splitting the video file into multiple small files and merging them after recording.

The whole process worked, but finally, I discovered AVAssetWriter has a lifesaving property called movieFragmentInterval. After setting the Fragment, it writes current metadata to the file at fixed intervals. This way, the file remains readable. And compared to HLS segmented saving, it has a huge advantage: it is single-file storage, no need to merge files after recording.

let assetWriter = try AVAssetWriter(outputURL: url, fileType: .mp4)

// Set to write fragments every 10 seconds, preventing total loss on crash

assetWriter.movieFragmentInterval = CMTime(seconds: 10, preferredTimescale: 600)Static Screen Recording Video Length Is Always Only 1 Second?

Users reported incorrect recording duration. They recorded for 10 seconds, but the file was only 1 second long.

After researching, I found this was due to a conflict between SCK’s energy-saving mechanism and AVAssetWriter’s writing mechanism.

To save power, SCK doesn’t generate new frames when the screen content is static. But AVAssetWriter is linear. If a frame is written at second 1, and recording ends at second 10 with no new data in between, the generated video file often judges the duration as only 1 second.

I initially wanted to use a timer to do “heartbeat frame filling,” but found it too complex and resource-intensive. The final solution was simple and crude: Manually patch the last frame at the moment recording stops.

[Solution]: When calling

stopRecording, take the cached “last frame image,” change its timestamp to “current end time,” and force write it. This way,AVAssetWriterknows: “Oh, so this image persisted until now.”

func stopRecording() async {

// 1. Stop receiving new data from SCK

stream.stopCapture()

// 2. Critical Step: Fill Frame

// If last write time was 00:01, and now is 00:10,

// we need to write the last frame again, but set timestamp to 00:10

if let lastSample = self.lastAppendedSampleBuffer {

let currentTimestamp = CMTime(seconds: CACurrentMediaTime() - startTime, preferredTimescale: 600)

// Create a new SampleBuffer, reusing image data, modifying time

let finalBuffer = createSampleBuffer(from: lastSample, at: currentTimestamp)

if assetWriterInput.isReadyForMoreMediaData {

assetWriterInput.append(finalBuffer)

}

}

// 3. Finish writing

await assetWriter.finishWriting()

}SCK Window Recording Cannot Record Sub-windows on Secondary Screen?

SCK can directly record a window (Window Capture). During recording, the window can be moved or hidden under other windows without affecting the recording. It’s very elegant. I’ve always used this mode, but I found that competitors weren’t using it, and I didn’t know why.

Once, I was recording content on a secondary screen. After recording, I found the right-click menu content was completely missing. After some tossing and turning, I found an extremely bizarre Bug: Using SCK’s Window Capture Mode, everything records normally on the MacBook main screen, and right-click menus (even though they are independent Window IDs) are captured. However, once dragging the window to a secondary screen to record, the right-click menu mysteriously disappears.

This is obviously a macOS framework layer Bug or some undocumented limitation (Sub-window capture fails on secondary screens).

Because of this, I immediately understood why competitors don’t use it. They’d rather sacrifice a bit of user experience than sacrifice user content. For us making content production tools, content integrity is the user’s root; content cannot be lost.

So quickly, I also switched to using Display Mode (Area Mode) to replace Window Capture Mode, giving up some recording flexibility in exchange for content integrity.

Why Does SCK Keep Throwing the 3821 Issue Interrupting User Recording?

Later, I don’t know if it was a system upgrade or just more system content, but I could never record persistently with the software. It always died quickly within 10 minutes.

At first, I thought I broke something. I tried many ways to solve it, eventually even rolling back a massive amount of code. Not until I rolled back to the previously released version did I realize: it wasn’t my code that changed, it was the environment.

I opened the old version with fear and trepidation, trying version by version, only to find it completely different from before. Not a single version could record continuously for more than 10 minutes.

The same error kept popping up in the console:

Error Domain=SCStreamErrorDomain Code=-3821

"The display stream was interrupted"My world collapsed.

When I exhausted all possibilities and couldn’t think of a reason, my brain started thinking about metaphysical questions: “This is fishy, maybe sleeping on it will fix it.”

Slept on it, everything remained the same.

I spent a long time troubleshooting, reproducing, and looking for patterns. But when I started searching for information, I found a very awkward fact: There is very little relevant information. Many problems look like “everyone has encountered them,” but almost no one can explain “why this happens,” and there are no reliable solutions online.

Scientific Experiment: Testing All Competitors

After being metaphysical for a long time, I finally remembered to try out competitors. I knew they used to run well. System built-in ones, mainstream commercial software, OBS, ffmpeg, and some meeting software—I dug out all the software I had tested before.

Those few days, I was like doing a scientific experiment:

- Same scene

- Same time period

- Same machine

- Switching different software to record, then seeing how they broke.

The test gave me a shock. Numerous competitors almost all died within the first ten minutes.

Fortunately, through this, I finally understood it wasn’t my fault, it was the timing. Different software handles SCK instability differently:

| Competitor/Tool | Behavior when encountering issues | User Experience |

|---|---|---|

| QuickTime… | Stops recording immediately, saves recorded part. | Sudden interruption, user confused. |

| Screen Studio… | Pops up error window, stops automatically. | Honest. Interrupted but protected user’s right to know. |

| OBS… | Picture freezes on last frame, but timer continues. | Worst. User thinks it’s recording, actually recording nothing (silent failure). |

| ffmpeg… | Dropped frames, stuttering, but stubbornly continues (because it defaults to Legacy mode). | Picture looks like a slideshow, but at least there’s content. |

This comparison experiment made me realize a rather counter-intuitive fact: For screen recording, “not interrupting” isn’t necessarily better than “interrupting”.

The worst pitfall is “silent failure”: It looks like it’s still recording (timer running, interface normal), but upon playback, you find the second half missing or the image repeating the same frame. The user thinks everything is normal but has actually entered silent failure. This is often more disastrous than immediate interruption because it deprives the user of the right to know at the most critical moment.

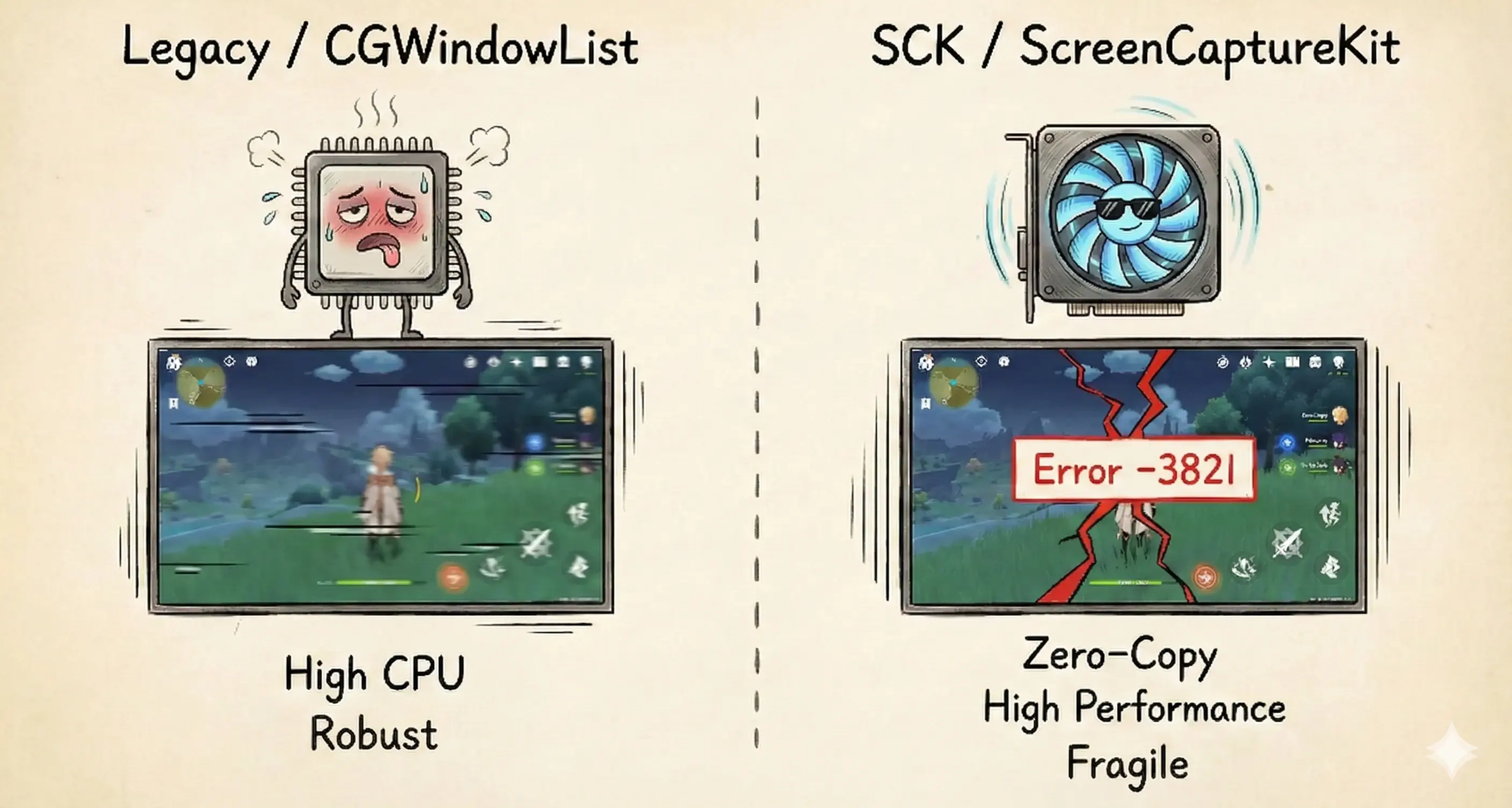

Technical Reason: SCK vs Legacy

Why is everyone so miserable? Why does ffmpeg behave differently?

After long periods of tinkering and observation, I roughly figured out the different behavior logic of ScreenCaptureKit (SCK) and traditional Legacy (CGWindowList) under high system pressure:

Legacy (Traditional Mode): Resilient

- When system load is high, it drops frames.

- Mouse lags, picture jumps, CPU usage spikes.

- But it grits its teeth and keeps the recording going, not disconnecting unless absolutely necessary.

SCK (New Framework): Brittle

- Pursues high performance and low latency, GPU zero-copy, low power consumption.

- Once system resources (VRAM or bandwidth) cannot meet its buffer requirements.

- It doesn’t degrade gracefully but throws a 3821 error and disconnects immediately.

This explains why there is no perfect solution yet, and why although ffmpeg has high CPU usage, it often (though falsely recording or stuttering) persists in working when SCK dies—because it defaults to Legacy mode.

My Coping Strategy

Facing this problem, I made several decisions:

1. Provide Legacy Alternative

Although Legacy mode has performance issues (high CPU usage, high power consumption), at least it guarantees recording integrity in extreme cases. So I provided a toggle option in the software, letting users choose between stability and performance.

2. Monitor Frame Drop Rate, Proactive Warning

Although I can’t completely stop the 3821 error, I can give users a heads-up before the problem gets serious.

I continuously monitor the frame drop rate during recording. When the drop rate rises abnormally, I proactively remind the user that the current system load is high and suggest they pause other applications or switch to Legacy mode. At least this gives the user the right to know, rather than finding out after recording.

3. Honest Error Reporting, No “Fake Recording”

I’d rather the product honestly stop and tell the user an error occurred than give the user the illusion of “seemingly recording.” Once a 3821 error is caught, stop recording immediately and prompt the user, while saving the recorded part.

4. The Voodoo Tip

There is a folk remedy circulating in the developer community (which I verified seems effective): Ensure system disk free space is greater than 12GB.

Ideally, this is because the WindowServer process relies on swap space (Swap) when handling large amounts of texture data. If disk space is tight, it’s easier to trigger buffer allocation failures, causing SCK to crash. Although it sounds metaphysical (voodoo), it indeed reduced the frequency of the problem. I added this suggestion to the software’s help documentation.

To this day, I still can’t say I “eliminated

-3821.” The root cause remains a mystery, the Apple official forums are full of wailing, and I haven’t found a clear verifiable “probability reduction method.” But at least, I can guarantee the product reacts to failure in a reliable, honest way.

SwiftUI Timeline Is So Laggy, How to Optimize?

Recording the screen is just the first step; users need to edit the video later. ScreenSage Pro provides a timeline editor similar to CapCut or Final Cut Pro, where users can adjust the duration, position, effects, etc., of each clip.

Initially, this feature worked fine, but as users recorded longer videos and the clips on the timeline increased (a 10-minute recording might have dozens of mouse click events, each corresponding to an editable clip), the problem appeared:

The interface started to lag.

Dragging the timeline dropped frames, modifying a clip’s property caused the whole interface to flicker. Most exaggeratedly, when there were 100+ clips on the timeline, simply scrolling the timeline felt like significant latency.

Root Cause: ObservableObject Global Refresh

Initially, my timeline data model looked like this:

class TimelineViewModel: ObservableObject {

@Published var clips: [TimelineClip] = []

@Published var currentTime: Double = 0

@Published var playbackState: PlaybackState = .paused

}

class TimelineClip: ObservableObject, Identifiable {

let id = UUID()

@Published var startTime: Double

@Published var duration: Double

@Published var zoomScale: Double

// ... more properties

}Looks normal, right? But the problem lies in @Published.

When I modify the zoomScale of a single TimelineClip (e.g., user adjusts zoom level of a clip), what does SwiftUI do?

It refreshes all views dependent on the clips array.

Even if most clips haven’t changed at all, even if a view only cares about currentTime and not clips, as long as there is any change in the clips array, SwiftUI thinks “the whole model changed” and triggers a massive view redraw.

100 clips = 100 unnecessary view updates. This is the root cause of the lag.

Solution: Migrate to @Observable

In WWDC 2023, Apple introduced the new @Observable macro (iOS 17+ / macOS 14+), which solves exactly this problem.

I changed the code to this:

// New Solution: Using @Observable

@Observable

class TimelineViewModel {

var clips: [TimelineClip] = []

var currentTime: Double = 0

var playbackState: PlaybackState = .paused

}

@Observable

class TimelineClip: Identifiable {

let id = UUID()

var startTime: Double

var duration: Double

var zoomScale: Double

// ... more properties

}Looks like just removing @Published and ObservableObject? But the underlying mechanism is completely different.

Why is @Observable faster?

@Observable uses Fine-Grained Property Tracking:

- SwiftUI knows precisely which properties each view depends on.

- A view redraw is triggered only when a property actually used by that view changes.

- If a view only reads

clip.duration, then modifyingclip.zoomScalewill not trigger its update.

For example:

// This view only depends on duration

struct ClipDurationLabel: View {

let clip: TimelineClip

var body: some View {

Text("\(clip.duration, specifier: "%.2f")s")

}

}- Old Solution (ObservableObject): Modifying

clip.zoomScalecauses this view to refresh. - New Solution (@Observable): Modifying

clip.zoomScaletriggers no update because this view doesn’t use it at all.

This is the secret to the performance skyrocket.

Migration Effects

After migrating to @Observable, the performance improvement was immediate:

- Scrolling Timeline: From dropped frames to silky 60fps.

- Modifying Clip Properties: From global flicker to local update.

- 100+ Clips Scenario: From obvious lag to almost imperceptible.

Pitfalls During Migration

Although @Observable is great, I stepped into a few holes during migration:

1. Not a mindless replacement

@Observable cannot directly replace ObservableObject, especially initialization:

ObservableObjectuses@StateObject(initializes only once).@Observableuses@State(if written improperly, might initialize multiple times).

My solution was to move initialization logic to the parent view to avoid accidental duplicate creation.

2. Combine related code needs rewrite

@Observable no longer uses objectWillChange. If you have logic depending on this, it needs implementation in other ways. Fortunately, my timeline editor didn’t have much Combine code, so migration was smooth.

Summary

If your SwiftUI app has similar scenarios—large lists, complex data models, frequent local updates—I strongly recommend migrating to @Observable. It’s not just syntactic sugar, but a qualitative leap in SwiftUI performance optimization.

The only limitation is requiring iOS 17+ / macOS 14+, but for new projects, this isn’t an issue.

Conclusion

Looking back at this year-long development journey, from the anxiety during pre-sales to the gradual stability of the product now, it feels like going through a long level-clearing game.

Some levels were passed smoothly: finding the sweet spot BPP for video encoder bitrate; solving timeline performance with @Observable; figuring out the logic of first-frame timestamps for sync. These problems, while headache-inducing at the time, at least had clear solutions—research, experiment, change code, conquer.

But some levels haven’t been perfectly cleared yet: SCK’s 3821 error still appears periodically, and I can only fallback to Legacy mode; the bug of recording sub-windows on secondary screens is a system framework issue I can only bypass; segmented recording reduces risk but cannot 100% guarantee no data loss.

At first, I was anxious about these “unsolved” problems, feeling the product wasn’t perfect. But after working on it for a year, I’ve come to understand:

Not all problems have standard answers.

Sometimes you have to accept system limitations, sometimes you have to balance between performance and stability, sometimes you can only achieve “honest error reporting” instead of “never failing.” These sound like compromises, but they are actually maturity—a shift from “I want to make a perfect product” to “I want to make a usable product.”

Now ScreenSage Pro has users using it to record tutorials, do demos, and edit videos. Although I still occasionally receive Bug reports, and although there are many features I want to build but haven’t had time for, seeing users actually using it to solve problems is a wonderful feeling.

The code you write runs out of your computer, lands on someone else’s computer, saving them time and solving their troubles. This is probably the greatest meaning of making products.

If you are also doing independent development and struggling with various technical issues, I hope this article gives you some inspiration. Not necessarily specific technical solutions (after all, every product encounters different pits), but a mindset:

Best if solvable, if not, find a workaround. Don’t let perfectionism drag down progress.

Done is better than perfect.