For a long time, developers had many complaints about SwiftUI’s early navigation system (NavigationView). Due to its inherent limitations, implementing basic features—such as returning to the root view, pushing arbitrary views onto the stack, jumping back multiple levels, or handling Deep Links—often required “hacks” or complex workarounds. Starting with iOS 16 and macOS 13, SwiftUI introduced a modern API centered on view stack management, making programmatic navigation intuitive and straightforward. This article will explore this modern navigation system in depth.

Divided into Two: Purpose-Built Navigation Controls

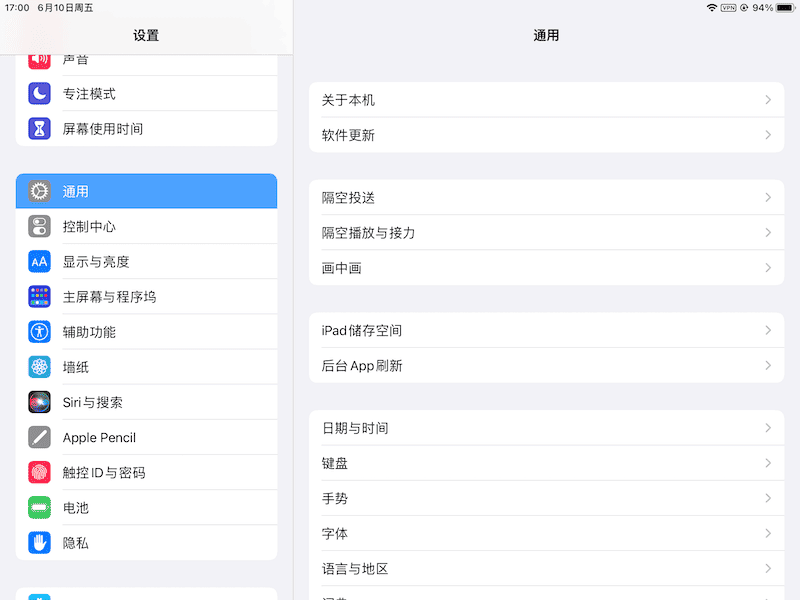

The most immediate change in the modern navigation system is the replacement of NavigationView with two distinct controls: NavigationStack and NavigationSplitView.

NavigationStack is designed for single-column scenarios, such as iPhone, Apple TV, and Apple Watch:

NavigationStack {}

// Equivalent to the legacy:

NavigationView {}

.navigationViewStyle(.stack)NavigationSplitView is designed for multi-column scenarios, such as iPadOS and macOS:

NavigationSplitView {

SideBarView()

} detail: {

DetailView()

}

// Corresponding to a two-column scenario:

NavigationView {

SideBarView()

DetailView()

}

.navigationViewStyle(.columns)

NavigationSplitView {

SideBarView()

} content: {

ContentView()

} detail: {

DetailView()

}

// Corresponding to a three-column scenario:

NavigationView {

SideBarView()

ContentView()

DetailView()

}

.navigationViewStyle(.columns)

Compared to the old way of setting navigationViewStyle, this split-control approach makes the layout intent much clearer and encourages developers to better adapt their SwiftUI apps for iPadOS and macOS.

On devices like the iPhone,

NavigationSplitViewautomatically adapts to a single-column layout. However, it differs significantly fromNavigationStackin terms of transition animations and programmatic API interfaces. For apps supporting multiple platforms, it is best to use the specific navigation control that fits each use case.

Modern Programmatic Navigation Logic

Beyond the name changes, the enhancement of programmatic navigation is the true highlight of this update. Developers can now easily implement features like returning to the root, pushing arbitrary views onto the current stack, or external navigation (Deep Linking).

Apple provides two different programmatic logic styles for NavigationStack and NavigationSplitView, which may cause confusion for some developers.

Traditional Programmatic Navigation (Legacy Way)

NavigationView did have some programmatic capabilities. For example, we could use the following NavigationLink constructors for limited programmatic jumps:

init<S>(_ title: S, isActive: Binding<Bool>, @ViewBuilder destination: () -> Destination)

init<S, V>(_ title: S, tag: V, selection: Binding<V?>, @ViewBuilder destination: () -> Destination)These methods had significant limitations:

- They required binding view by view; returning to an arbitrary level required manual state management.

- You had to declare the destination view inside the

NavigationLink, causing unnecessary view instance creation. - Calling navigation from outside the view hierarchy was difficult.

“Usable, but not good” is perhaps the most apt summary of the old programmatic navigation.

NavigationStack: Type-Based Reactive Navigation

For example, the following code shows a common way to handle programmatic jumps in the legacy API:

struct NavigationViewDemo: View {

@State var selectedTarget: Target?

@State var target: Int?

var body: some View {

NavigationView {

List {

// SwiftUI creates instances of SubView1/2 upon entering this view,

// even if they aren't pushed (though it doesn't evaluate their body).

NavigationLink("SubView1", destination: SubView1(), tag: Target.subView1, selection: $selectedTarget)

NavigationLink("SubView2", destination: SubView2(), tag: Target.subView2, selection: $selectedTarget)

NavigationLink("SubView3", destination: SubView3(), tag: 3, selection: $target)

NavigationLink("SubView4", destination: SubView4(), tag: 4, selection: $target)

}

}

}

enum Target {

case subView1, subView2

}

}NavigationStack implements this more cleanly, flexibly, and efficiently:

struct NavigationStackDemo: View {

var body: some View {

NavigationStack {

List {

NavigationLink("SubView1", value: Target.subView1) // Only declare the state value

NavigationLink("SubView2", value: Target.subView2)

NavigationLink("SubView3", value: 3)

NavigationLink("SubView4", value: 4)

}

.navigationDestination(for: Target.self) { target in // Unified handling for a type

switch target {

case .subView1: SubView1()

case .subView2: SubView2()

}

}

.navigationDestination(for: Int.self) { target in // Multiple blocks for different types

switch target {

case 3: SubView3()

default: SubView4()

}

}

}

}

enum Target {

case subView1, subView2

}

}Advantages of the NavigationStack approach:

- Efficiency: Since you don’t specify the destination view inside

NavigationLink, no redundant view instances are created. - Centralization: Manage all navigation logic driven by the same type in one place (e.g., at the root view), which is great for complex logic and code separation.

- Priority:

NavigationLinkuses the nearestnavigationDestinationdefinition. If both the root and a subview define a handler forInt, the subview’s handler will take priority for itself and its children.

Manageable View Stacks: NavigationPath

While type-based reactive destination handling is great, the truly powerful feature is the Manageable View Stack System.

NavigationStack supports two types of stack management:

1. NavigationPath

By using NavigationPath, a NavigationStack can respond to multiple types of Hashable values. You can use removeLast(_ k: Int = 1) to go back specific levels or append to push new levels.

class PathManager: ObservableObject {

@Published var path = NavigationPath()

}

struct NavigationViewDemo1: View {

@StateObject var pathManager = PathManager()

var body: some View {

NavigationStack(path: $pathManager.path) {

List {

NavigationLink("SubView1", value: 1)

NavigationLink("SubView2", value: Target.subView2)

NavigationLink("SubView3", value: 3)

NavigationLink("SubView4", value: 4)

}

.navigationDestination(for: Target.self) { target in

switch target {

case .subView1: SubView1()

case .subView2: SubView2()

}

}

.navigationDestination(for: Int.self) { target in

switch target {

case 1: SubView1()

case 3: SubView3()

default: SubView4()

}

}

}

.environmentObject(pathManager)

.task {

// Programmatically jump multiple levels: root -> SubView3 -> SubView1 -> SubView2

// Adding levels during initialization disables the transition animation.

pathManager.path.append(3)

pathManager.path.append(1)

pathManager.path.append(Target.subView2)

}

}

}

struct SubView1: View {

@EnvironmentObject var pathManager: PathManager

var body: some View {

List {

NavigationLink("SubView2", value: Target.subView2)

NavigationLink("subView3", value: 3)

Button("Go to SubView3") {

pathManager.path.append(3)

}

Button("Back to Root") {

pathManager.path.removeLast(pathManager.path.count)

}

Button("Back One Level") {

pathManager.path.removeLast()

}

}

}

}2. Single-Type Sequence (Hashable)

Using a standard array of a specific Hashable type limits the stack to only responding to that specific type.

class PathManager: ObservableObject {

@Published var path: [Int] = [] // Hashable sequence

}

struct NavigationViewDemo1: View {

@StateObject var pathManager = PathManager()

var body: some View {

NavigationStack(path: $pathManager.path) {

List {

NavigationLink("SubView1", value: 1)

NavigationLink("SubView3", value: 3)

}

.navigationDestination(for: Int.self) { target in

// Handle Int types...

}

}

.task {

pathManager.path = [3, 4] // Directly jump to specific depth

}

}

}⚠️ Warning: When using the stack management system, avoid mixing programmatic navigation with legacy declarative navigation (

NavigationLink(destination:)), as it can break the stack data.

// AVOID THIS:

NavigationLink("SubView3", value: 3)

NavigationLink("SubView4", destination: { SubView4() }) // Mixing will cause stack resetsNavigationSplitView

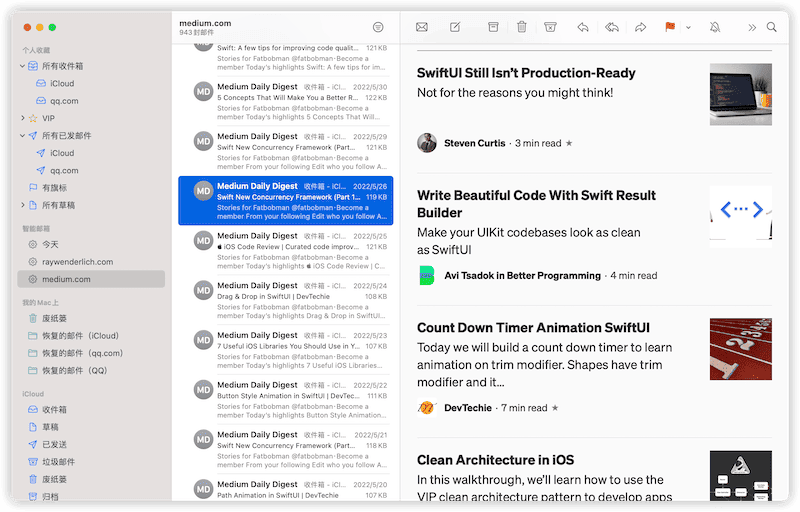

While NavigationStack stacks views in 3D space, NavigationSplitView dynamically switches views across panels in 2D space.

Multi-Column Layout

Before SwiftUI 4.0, creating a two-column programmatic navigation looked like this:

class MyStore: ObservableObject {

@Published var selection: Int?

}

struct SideBarView: View {

@EnvironmentObject var store: MyStore

var body: some View {

List(0..<30, id: \.self) { i in

Button("ID: \(i)") {

store.selection = i // Change selection to update detail

}

}

}

}With NavigationSplitView, the logic remains similar, but the modern List provides built-in data binding:

struct SideBarView: View {

@EnvironmentObject var store: MyStore

var body: some View {

// Direct binding in List

List(0..<30, id: \.self, selection: $store.selection) { i in

NavigationLink("ID: \(i)", value: i)

}

}

}In modern SwiftUI, if a List is bound to data, loop content (like Text or Label) that doesn’t have its own tap gesture will be implicitly treated as a selectable item.

Collaboration with NavigationStack

A common pain point in the legacy NavigationView was embedding a stack inside a Detail column, which often resulted in duplicated Navigation Titles and Toolbars. NavigationSplitView solves this by perfectly coordinating with NavigationStack.

struct NavigationSplitViewDoubleColumnView: View {

@StateObject var store = MyStore()

var body: some View {

NavigationSplitView {

SideBarView()

} detail: {

DetailView()

.toolbar { EditButton() }

.navigationTitle("Detail")

}

}

}

struct DetailView: View {

@EnvironmentObject var store: MyStore

var body: some View {

NavigationStack {

VStack {

if let selection = store.selection {

NavigationLink("View Details", value: selection)

}

}

.navigationDestination(for: Int.self) { Text("\($0)") }

.toolbar { RenameButton() } // Merged with the SplitView toolbar

.navigationTitle("Detail Inline")

.navigationBarTitleDisplayMode(.inline)

}

}

}NavigationSplitView retains the most recent Title setting and merges toolbar buttons from both the NavigationSplitView and the inner NavigationStack.

Dynamic Column Visibility

NavigationSplitView allows programmatic control over column visibility via the columnVisibility parameter (NavigationSplitViewVisibility):

- detailOnly: Shows only the detail (rightmost) column.

- doubleColumn: In a three-column setup, hides the Sidebar (leftmost).

- all: Shows all columns.

- automatic: Automatic behavior based on context.

Other Enhancements

The modern navigation system includes several other powerful features:

Setting Column Width

Use navigationSplitViewColumnWidth to customize column sizing:

SideBarView().navigationSplitViewColumnWidth(200)

ContentColumnView().navigationSplitViewColumnWidth(min: 100, ideal: 150, max: 200)NavigationSplitView Styles

Use navigationSplitViewStyle to adjust the layout:

- balanced: Reduces the detail column size when showing sidebars (default for iPad Landscape).

- prominentDetail: Maintains the detail column size regardless of sidebars (default for iPad Portrait).

Menus in Navigation Titles

Embed a menu directly into the title bar:

.navigationTitle(Text("Settings"), actions: {

Button("Action 1") {}

Button("Action 2") {}

})Navigation Bar Backgrounds

Change the background color of the toolbar:

.toolbarBackground(.pink, in: .navigationBar)The background usually appears when content scrolls behind it.

Toolbar Roles

Use toolbarRole to define the character of the toolbar (e.g., .editor hides the previous view’s title next to the back button; .browser moves the title to the left on iPad).

NavigationLink as a Button

NavigationLink is now truly treated as a button, allowing you to apply standard button styles:

NavigationLink("Hello", value: "sub1")

.buttonStyle(.borderedProminent)

.controlSize(.large)Summary

The modern SwiftUI navigation system represents a major milestone in the framework’s maturity, providing the programmatic control and flexibility needed for complex app architectures. While developers still supporting older OS versions may need to use tools like NavigationBackport, those working on iOS 16+ or macOS 13+ should fully embrace NavigationStack and NavigationSplitView.

This system not only offers powerful control over the view hierarchy but also guides developers toward creating adaptive UIs that feel native to both small and large screens.